Vulnerable in Bastar

The arrest of Dantewada-based journalist Prabhat Singh in Bastar in Chhattisgarh on Monday evening has, yet again, brought into focus the vulnerability of dissenting journalists in this conflict zone. But it is also a telling indication of the polarisation of the media in the area as this intensely divisive conflict has pitted journalists against one another.

Prabhat Singh, who was working as a stringer with ETV channel and Rajasthan Patrika and is part of a journalists’ solidarity forum on attacks in the media in the Bastar region, was arrested on charges of obscenity under Sec 292 A of the Indian Penal Code and Sec 67 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. He has been remanded to judicial custody till March 26. Singh is the third journalist, after Santosh Yadav and Somaru Nag, to be arrested in this region.

Singh’s arrest is also a grim portent of the potential of yet another section of the Information Technology Act – Sec 67 which deals with obscenity - to harass and intimidate free expression. Last week, two youth Shakir Yunus Banthia and Wasim Sheikh, were arrested in Khargone in Madhya Pradesh for sharing a morphed Whatsapp picture of RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat with the torso of a woman wearing brown trousers. The duo was charged under Sec 67 of the IT Act as well as Sec 505(2) of the IPC, dealing with statement that can promote enmity between classes. Both sections can result in a maximum jail term of three years.

According to reports filtering in from Bastar, it appears that a fellow journalist and administrator of a Whatsapp group, Santosh Tiwari, complained to police about Prabhat Singh’s messages that allegedly poked fun at the controversial Inspector General of Bastar range SRP Kalluri, against whom there are allegations of torture and harassment of adivasis on the pretext of containing the Maoist insurgency in the region. Singh allegedly referred to Kalluri as ‘Kallu Mama’ in a Whatsapp group for members of the media (Kallu mama was the name of a character who plays a gangster in the Hindi film ‘Satya’).

While Tiwari’s phone was switched off, other members of the group told The Hoot, on condition of annonymity, that journalists in the group were close to the Swabhiman Ekta Manch and had taken objection to his comments. Asked why the group administrator didn’t resort to other means to contain offensive comments, warn or even remove Singh from the list of participants, there was no response. This is the local NGO which attacked Scroll writer Malini Subramanian’s property earlier this year.

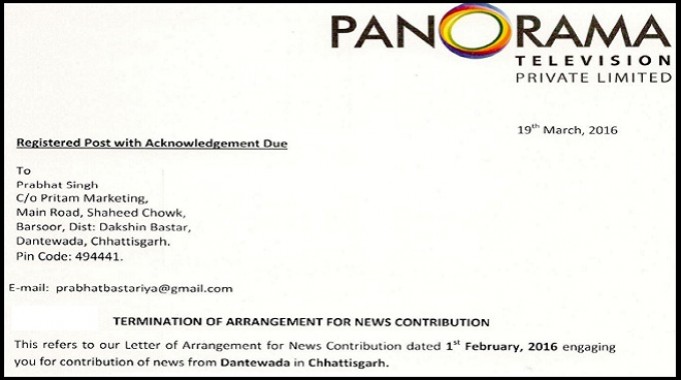

Curiously, barely three days before his arrest, Singh’s services were terminated by ETV, on ground that he violated clause no 7(iii) of the ‘arrangement for news contribution’. This however finds no mention in his letter of termination in which no grounds are given. His friends feared that his services were terminated on pressure from Bastar police in retaliation for his active role in the journalists’ safety committee that had been campaigning for the release of arrested journalists Yadav and Nag. They had also raised a voice of protest at the hounding of Malini Subramaniam. He also spoke out at the attack on adivasi leader Soni Sori.

However, a senior editor at the news channel told The Hoot, on condition of anonymity, that the termination was not effected under pressure from the police but because Singh did not possess a camera! “As a stringer, he was expected to possess and use a video camera. He assured us he would obtain one but did not do so even after two months into the job. Whenever he had to shoot visuals of news, he sent videos shot on a mobile camera which was not good enough for broadcast,” the editor said. The arrest of the journalist so soon after the termination was just a coincidence, the editor asserted.

In Bastar, a bloody conflict between security forces and Maoists has been underway for several years now and journalists have to withstand immense pressures to report freely and independently about it. Journalists have been caught in the crossfire, three have been killed by Maoists on charges of being police informers. Other journalists have been attacked and intimidated by various so-called social service outfits that openly work with local police.

In 2010, a vigilante group called the Maa Danteshwari Adivasi Swabhiman Manch threatened three journalists of Dantewada, the veteran NRK Pillai, Anil Mishra and Yaashwant Yadav. The Superintendent of Police in Dantewada was then none other that the current IG of Bastar, SRP Kalluri. Asked by this writer what he was doing to protect the three who were threatened, he preferred to call them ‘black sheep’ and said he had no time for such rubbish!

Last month, Malini Subramaniam, along with lawyers Shalini Gera and Isha Khandelwal of the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group, was forced to leave Jagdalpur on February 19, when the landlords of their respective premises served them eviction notices, allegedly at the behest of local police. Barely three days later, on February 22, the BBC Hindi correspondent from Chhattisgarh Alok Putul was forced to abandon an assignment midway due to a veiled threat from Kalluri that said that police in Bastar had the support of local ‘nationalist’ media and did not need media from outside Bastar!

While the statements hardly inspire confidence in the responsibility of the police to enforce law and order, what does this mean for journalism in Bastar? For one, there will be no independent reportage of the ground situation. As it is, local journalists say that only those favoured by the police go on helicopter sorties over the conflict zone, much like embedded journalists in war zones. Expressing serious apprehensions in a statement, the Chhatisgarh unit of the People Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) said that ‘the police and district administration are trying to silence all journalists who are attempting to give any other version of events in Bastar other than the police version’.

Referring to the killing of villagers in IED blasts in the area over the last two weeks, the Chhattisgarh PUCL statement reiterates its demand that, ‘in order to protect non-combatant civilians in this war zone, the Government of India should declare a state of internal armed conflict and allow strict independent monitoring under the Geneva Protocol of human rights violations by both parties to the conflict’.

Will this help the media to operate freely in the area and cover the conflict without threat from either the security forces or the Maoists? Perhaps it may provide equal access to all journalists, irrespective of their own views. Indeed, the lines being drawn along notions of nationalism and political support to insurgency movements, whether in Maoist areas of central India or in the North East or Kashmir, is undoubtedly straining the frameworks of free and fair media coverage. Journalists need to speak out for their colleagues under attack, instead of providing fodder for state authorities that seek to divide them.